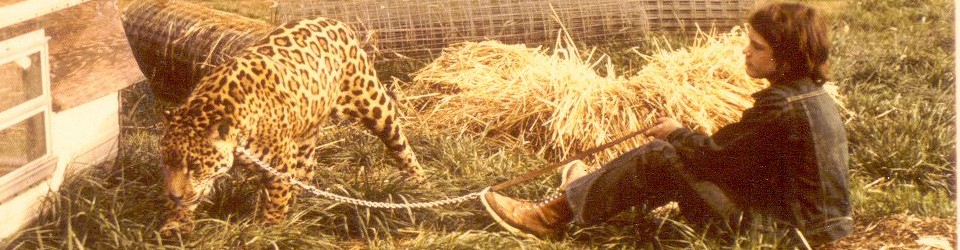

When I first met Mike, the man who would become my stepfather, he had a foster daughter named Diane. As a teenager, she was too much for her parents to handle so Mike, who had a way with wild things, took her in. She left the farm about the time I arrived, taking Moses, her Neapolitan mastiff, with her. And some time after that, she got a second dog, a young Irish wolfhound she named Jason.

One evening, Diane showed up unexpectedly at the door of the farmhouse. She was crying and panicky. The night before, her mastiff had suddenly started bleeding from his rectum and died. She found a note that read, “We got your dog. Tonight we’re coming back for the other one.”

“They must have fed him ground glass,” said Diane. She was certain that whoever killed Moses planned to do something similar to Jason, the wolfhound puppy. She told us she had been living with a member of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club and had left her “old man” without his blessing. Knowing a little about Dianne’s past, I wondered if there was more to the story, but clearly Diane had pissed off some badass biker and was afraid for herself as well as for Jason.

We sat around the table—my mother, Mike, Diane and I—and discussed options. One possibility was for someone to go home with Diane and stay up all night to keep watch—and to fight off the Hells Angels if they showed up.

I volunteered, even though I was only sixteen, was about five foot three, weighed at most 115 pounds, and had never been up all night. Nor, for that matter, had I ever been in a gunfight or serious fight of any kind. Plus, I had been born with a genetic defect that means I don’t take particularly well to gunshot wounds. I have hemophilia, a bleeding disorder, and I had gotten to that point in my life only by ignoring limitations. I had always insisted I could do anything, no matter what anyone else might say. When my parents told me I couldn’t have a bike without training wheels, for example, I borrowed a teenage neighbor’s six-speed and taught myself to ride even though I couldn’t reach the seat.

So while Mike, Diane, and my mother continued talking (on the surface at least, they appeared to giving the option of sending me serious consideration) I went into the master bedroom, unlocked the gun cabinet, and started arming myself. As a novice, I had no idea what kind of weapons I would need. Would I be shooting to warn, to wound, or to kill? Would the fighting be close in, or would I need a weapon with range? Would there be one biker or many? Since I had no answers, I prepared for any possibility.

I strapped on two shoulder holsters. Under the left arm, I shoved Mike’s untraceable Colt .45, and under the right a nine-millimeter Browning. I also belted a tiny .25 caliber automatic to one leg. I chose an over-under as my main gun. The top barrel fired a .22 longshot rifle round and the bottom fired a .410 shotgun shell. My hope was that I would not need anything too lethal. Still, I thought, I might require something more, just in case things got nasty. Just in case I needed to kill someone.

I was trying to decide between the Winchester Model 12 shotgun and the Weatherby big game rifle when my mother came in.

“We have decided to send Huxley instead,” she said, referring to one of Mike’s dogs, an English mastiff that weighed more than two hundred pounds. “He is trained to never take food from strangers.” She also pointed out that I had a math test the next day. “You need to study,” she said, as if this was the deciding factor.

I started unloading the weapons and stripping off the shoulder holsters. I was relieved and disappointed. If I had gone off to fight the Hells Angels, I might have gotten out of my test.

I told this story to someone once who responded, “It is a story about something that didn’t happen.” And to an extent that’s true. I didn’t end up in a gun battle. But it is also a story about something that did happen. It is one of those “what the hell were the parents thinking?” stories, but it is also a story about a sixteen-year-old thinking it was appropriate to arm for battle like that.

To understand why, I have to tell another story, one about my time in the basement.

In the summer before sixth grade, my family moved into a house with a partially finished basement. I spent a lot of time those days with swollen ankles, kind of like very bad sprains, but for me they seemed to happen spontaneously. When the pain got so bad I couldn’t sleep, I would spend my nights down there watching television. We didn’t have 24/7 television in those days, and when the last station went off the air, usually around midnight, there would be a brief image of a waiving flag and the playing of the national anthem, and then nothing but a cross-like test pattern, and a steady tone. Staring at that pattern and listening to that tone for hours on end, I would swear to god, any god, that I would believe, I would pray, I would serve, if only he—or she—would take the pain away. It never worked; I never did find religion.

Many nights, I didn’t fall asleep until sunrise. I asked myself a lot of questions during those long vigils. By this time, I had stopped asking, pointlessly, “Why me?” Instead, I played out scenarios in my head. In one, I was in a life raft with several other people, but the raft would not stay afloat with all of us in and there wasn’t enough food and water to go around. Someone would have to go overboard into the frigid sea where the sharks were circling. I asked myself if I could be the one to jump, whether I would have the strength. Yes, is the answer that came back to me over and over. Yes.

I asked other, similar questions. For example, could I jump off a cliff if it would save lives? The answer was always yes. Meanwhile, my family slept soundly upstairs because I had taken it on myself to jump into the basement, where sharks shredded my ankles and I refused to cry out because I might wake them, adding to their burden.

Amid all these questions about sharks and cliffs, there was one question I never asked: Are these the kinds of questions a ten-year-old should be dealing with? But they were exactly the questions a boy might ask if he was ashamed and needed to justify being here.

You see, I didn’t feel I deserved to stay in the life boat, not unless there was room for everyone else. After all, I was defective. I had been born broken. How could I supplant someone who had a full life to look forward to, someone whole and normal? The best possible resolution to my situation, it seemed, would be to die a noble death. I didn’t think about suicide, that would have seemed cowardly and pointless, but I did think about making the ultimate sacrifice. It would offer redemption, wash away my shame, validate my existence.

These scenarios, these questions, were my own kind of test pattern, my own calibration.

That night when Dianne came over to tell us Moses was dead and asked for our help, I had been briefly offered the possibility of actually living out the kind of scenario I obsessed over all those nights in the basement—the possibility of dying in a hail of bullets to protect a woman and her puppy.

.

Craig McLaughlin

Author, performer, public speaker