In the summer of 1986, eighteen months after my HIV diagnosis, my friend Susan said she wanted to drive to Seattle, following Highway 1 up the coast. “I don’t have anyone to go with,” she said, “but if I have to, I’ll go alone.” That was all the invitation I needed.

We spent the first night in Arcata, and the next day we drove up Route 1 until we found a beach that would be perfect for the next event on our itinerary. The parking lot was full, but the day was windy and breezy, and people were sticking close to their vehicles.

In a clear patch of dry sand on the far end of the beach, we settled down out of the wind and out of sight of the parking lot. Reaching into her pocket, Susan brought out a bag of gelatin capsules filled with white powder. “I find that one usually isn’t enough,” she said. “I start with one and a half. When I start to feel the drug wear off, I take the other half, just to stretch the trip out a bit.”

Ecstasy had just been outlawed that year, but it was still widely used by therapists. Though it was showing up more and more at parties, some people saw it as a tool for personal growth. Susan was one of those people.

I had never tried it, but I knew it was working when I realized I was free from anxiety. The wind no longer nagged at me. Sunburn wasn’t a problem, because I had made peace with the sun the way a firewalker makes peace with the coals. I wasn’t concerned that some tourist might guess what we were up to. And I stopped worrying about the gear in Susan’s car, which had a busted trunk.

What I remember most was a feeling of safety. It was the perfect afternoon on the perfect beach with the perfect companion, and there was nothing that needed to be done except to enjoy every moment.

When the drug wore off, the feeling of perfection ended. My body had metabolized the drug into toxins that raided my stores of essential vitamins and minerals. My mouth was dry, and I couldn’t stop flexing my jaw. I was tired, very tired. Susan settled me into the passenger seat, found a campground, fed me tuna-fish sandwiches, and cleaned up while I crawled into my sleeping bag. Within minutes I was dreaming. My Continental flight to La Guardia was landing at the TWA terminal at Newark.

That was the last good rest I had for days. I found it hard to sleep when the dreams came. The basic plot was always the same. I desperately needed to get somewhere—where, exactly, was never clear—and was constantly thwarted. The shuttle wouldn’t take me to my connecting flight; the southbound train headed north out of the station; the downtown local turned into an uptown express. I initially considered the dreams unimportant, but in hindsight the clues were there: the repetition, the vividness, the overwhelming sense of frustration that forced me awake, and the way the dreams refused to fade.

Our days were largely uneventful. In a small coastal town, a dog ran across the road in front of us. We barely missed it, and the incident shook us both. When we reached Seattle, we got lost. Numbered streets and numbered avenues wove in and out of one another.

On the first day of our return trip, we took a detour up into the mountains and found a campsite on the shore of a small lake. There my dreams began to change.

In one, I sat at table with a group of coworkers. On the table lay a birthday cake decorated with the face of a clown. We had been waiting for the boss to show up so that we could begin. “We have to wait,” said one coworker. “He’ll be really angry,” said another. Then I surprised myself by driving my hand into the middle of the clown’s face. My fist came away full of cake, and I shoved it into my mouth. A cheer went up around the table, and I woke up laughing. The elation was so electrifying that it took me nearly half an hour to fall asleep again.

The second dream began on the edge of a lake. There was to be a picnic, and our meal was cooking in a Franklin stove. “What’s inside?” I asked.

“A goose,” someone answered. “They’re cooking a goose.”

A small animal appeared at the water’s edge. It wasn’t quite like anything I had seen before. It might have been a fox or a weasel or a dog. Whatever it was, it went to the stove, pushed open the door with its snout, and dragged out the goose. I grabbed a gun from someone nearby and fired. The bullet made the fox explode into dozens of foxes, all of which turned on me and began to nip, shredding my pants and tearing skin from my ankles.

I jumped into a car and drove away along a dirt road. I knew I’d be all right if I could get to the highway. In the distance I could see the glow of a Waffle Shop sign, a sure indicator of a highway interchange, but I couldn’t find a way to cut over. I was lost again. Suddenly the original fox appeared in the middle of the road. I didn’t have time to stop and wasn’t sure that I wanted to. The car jolted as it struck the fox, and I heard bones break under the wheels. When I came to a stop, I turned to look back.

Until that point in my life, I had never noticed whether I dream in color. Some people do and some don’t. I do. The moonlit sky was purple. The trees that lined the road were a green so deep they were almost black. The fox glowed a reddish orange as it rested on its haunches in the middle of the yellow road, and the eyes that taunted me were a brilliant, piercing green. In front of the fox was a crumpled human shape; it wasn’t white so much as without color, like a shadow in a photographic negative. Beside this shape lay a cane. The only thing in the scene that didn’t have a color was the scream that echoed off the night sky.

A couple weeks later, when I told Susan about the dream, she asked, “So who did you run over? Who was in the road?”

I told her I was pretty sure it was my father.

She took a sip of beer before asking the one question that mattered right then. “Does your father use a cane?”

As I answered no, a shudder passed through me—dread combined with the same elation I felt when I smashed the birthday cake. I knew where I had to get to. That place that was so hard to find. That place the boss didn’t want me to see. The place that was too scary too visit before the ecstasy.

I knew who lay dead in the road. At that point in my life, my left knee was really bothering me. I was using a cane.

In that moment, I truly confronted my own death for the first time.

The following weeks were some of the best of my life. I woke up enthused about each new day. I exercised, ate healthy meals, and lost weight. I contacted old friends whose phone calls and letters had gone unanswered for far too long.

Susan wasn’t finished with me, though. In September she called to say that the Berkeley Art Museum was featuring a show of Francesco Clemente, and she wondered whether I would like to go. Clemente didn’t make much of an impression on me, so I wandered off and entered an exhibit called Japanese Ghosts and Demons: Art of the Supernatural.

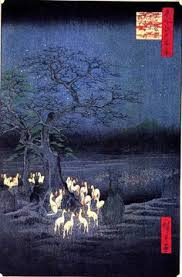

I was drawn immediately to Fox Fire, a 19th century print by Andō Hiroshige. The work is a representation of fox demons, or kitsune, common figures in Japanese folklore. A wall plaque explained that the fox demon is a trickster figure, and one role of the trickster is to force us to understand and accept aspects of ourselves that we might otherwise deny.

In the foreground of the print was a tree, and under the tree glowed dozens of stylized animals, each identical to the ones in my dream.

(NOTE: This story was first performed May 13, 2013 at The Shout Storytelling in Oakland.)

.