Note: I first presented this piece at Fireside Storytelling in San Francisco on Jan. 9, 2013. The theme was “Epic” and this story is about what felt like the longest car ride of my life. It has gone through a significant revision since the first telling.

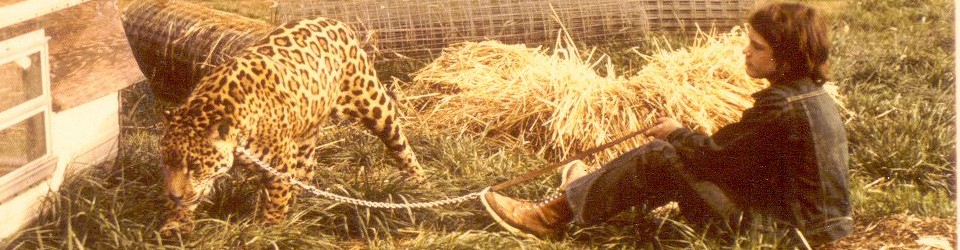

When I was in junior high, my mother and father split and my mother started seeing her graduate adviser a man named Mike. By senior high, I was living on Mike’s farm. About a year before I arrived, Mike went down to Florida and came back with a tiger. Next trip, he came back with a jaguar, and after that he just kept going until he had a private zoo populated mostly by big cats.

Maintaining his menagerie required frequent trips to buy, sell, trade, and loan animals, and I often went along. One of his regular stops was Cooke’s Buffalo Ranch in Concord, North Carolina. Cooke’s was a Western store. Old Man Cooke had a herd of bison in his pasture, and for a few bucks you could ride past them on a restored stagecoach. He also has a small roadside zoo.

On one visit we discovered the zoo had a new attraction—a chimpanzee named Lolita. (I don’t really want to think too hard about why someone would name a chimp Lolita.)

I thought I knew what chimps looked like, but what I had seen were a few movies and television shows. I didn’t realize that the trained chimpanzees were cuddly little juveniles.

Lolita, on the other hand was a young adult. She had black face and a mouth full of very large teeth that she displayed by curling back her lips. When she stood fully erect, she was taller than me. What struck me most was the power of her forearms, which seemed twice the length of mine, with thick, ropy cords of muscle. I knew that if I got too close, she could grab me, dismember me, and pull my body parts through the bars of her cage.

Lolita’s cage was a former drunk tank. The county had recently built a new jail, and Cooke had purchased the old drunk tank. It was a freestanding iron cell—an almost cube six feet wide on the sides but slightly taller, perhaps eight feet, in height. A tow chain wrapped around her neck and held in place with a padlock had chaffed away some of the hair.

It seemed a horrible way to live one’s life, but part of me was thankful for the bars, and maybe even for the chain. But then Old Man Cooke did something strange. He walked closer to the cage and stuck out his foot. Lolita reached through and gently, delicately untied his shoelaces. Then she tied them back again. Untie, tie, untie, tie, untie, tie. Cooke told us she would do this over and over again as long as you kept your foot next to her cage. I looked at the cage, I looked at the chain, I looked into her dark brown eyes. Seeing no hostility and a great deal of sadness, what else could I do? I offered her my sneaker.

A few weeks later, Mike informed us he had purchased Lolita. Tim, one of the regular weekend volunteers, had agreed to help move Lolita. Mike also made it clear that he was counting on my assistance, though I doubted there was much I could offer.

Tim arrived that day on his Harley Hog. When we climbed into the cab of the F350, Tim brought his motorcycle helmet with him. “Protection,” he said, pounding on it smugly.

At Cooke’s, we tied the end of Lolita’s chain to a post while Mike and Tim and some of Cooke’s workers loaded the tank into the bed of the truck. Mike decided it was too cool to transport Lolita inside her cage and his solution was to put her in the cab with us. It was a four door cab with two bench seats. He passed the free end of the chain through the split rear window and anchored it to the side of the bed. The chain kept Lolita from climbing into the front seat. It did nothing, however, to keep her from reaching across the seat and, if she chose, snapping me in half.

For the first part of the drive, Lolita occupied herself with dismantling the truck. She pulled out the dome light, unscrewed the door locks, and managed to yank loose one of the window cranks. Because her fidgeting made him nervous, Tim put on his helmet—and as soon as he did, Wham, Wham, Wham. Lolita repeatedly and forcefully whacked the back of Tim’s head. He sat there for the better part of an hour, absorbing blow after blow. The whole time, I tried to make myself invisible. Tim was a body builder. He was over six feet tall and probably weighed about 250 pounds—and he had a helmet. At that time, I probably weighed about 115 pounds and I had not yet reached my full stature of five foot six. I was a little guy with a skinny neck and no helmet. And I have hemophilia, a bleeding disorder. I quickly recalled all the stories I had ever heard about hemophiliacs dying from cranial hemorrhaging. If Lolita starts flailing on my head, I thought, surely I am a dead man.

Somehow, though, we survived. Mike and Tim unloaded the drunk tank in the middle of the yard and led Lolita into it. “Man,” said Tim as he was leaving, “I’m sure glad I brought my helmet.”

Later, we learned more about Lolita’s history. It seemed a man had trained a young chimpanzee to ride on the back of his motorcycle. He wrecked the bike and killed the chimp, so he bought Lolita as a replacement. Lolita was a too old to train and she hated riding on the motorcycle. Absolutely hated it. The man gave up and sold her to Cooke. Lolita wasn’t hitting Tim as much as she was hitting his helmet. If he hadn’t put it on, she would have left him alone. And I was never at risk.

Mike had no other place to keep Lolita, so he left her in the drunk tank. From time to time, he would take her out so she could exercise and he could clean her cage. He would lead her from the tank by the chain and tie her to one of the trees in the yard. One day, when he decided to put her back in her cage, she wasn’t ready to go. Imagine!

Mike insisted by yanking the chain, and she responded by biting him on the hand, practically severing his thumb. Mike didn’t miss a beat. With his intact hand, he picked up a beef bone the dogs had left in the yard and slammed it down on her head. I half expected to see her topple over, but instead she staggered momentarily and then raced contritely back into the tank. Mike shut the door, ran inside to grab a towel to wrap his hand in, and got my mom to drive him to the hospital.

When I think back on Lolita’s time with us, I am most struck by how much I feared her. It is what most people would expect, I think. But fear wasn’t really in my vocabulary. As a child with hemophilia, someone who could easily die by falling off a bicycle or mistiming a leap from the diving board. I never would have gone anywhere or done anything if I had grown up in fear. At the farm, it wasn’t good to show fear, especially when I was going into a tiger’s cage on crutches or waking to find a jaguar at the foot of my bed. It wasn’t that I wasn’t afraid, but I refused to acknowledge my fear, even to myself.

I think I feared Lolita because if I had been her, I would have attacked, and that’s why it always felt an attack was imminent. After all, her previous owner terrorized her. Cooke put her in chains and jailed her. To his credit, Mike eventually sold Lolita to a zoo, and I wondered if that was his plan all along, to get her away from Cooke and into a bigger place where she had her own kind for company. But I don’t know that for sure, and she couldn’t have known it either.

Tim triggered her PTSD when he put on his helmet. Mike led her around by a chain, and slammed a bone down on her skull when she fought back. And me? Could I claim innocence because I was just along for the ride?

Fear is a complex emotion. Sometimes it is simply about preservation, but I think it can also be a secondary emotion. Like anger, it can mask something deeper. Perhaps in my case, that something was guilt.

I don’t think I feared Lolita more because she was any deadlier than the other animals I worked with, or because she was at heart a wild and uncontrollable beast. I think I feared her because she was so damn human..

Passing on Curves

NOTE: I first performed this piece at Fireside Storytelling in San Francisco in December 2012.

When I am in the woods for more than a day or two, everything slows down. I stop talking, I enter a trancelike state. My friends once made the mistake of letting me drive home like that. I was on a narrow, winding highway, a cliff face on one side and a steep drop on the other, making good time despite heavy truck traffic, when my girlfriend looked over and said, placidly, “I trust you. I know you know what’s around the bend. But some of us might be more comfortable if you didn’t pass on curves.”

This is a story about passing on curves.

When I was born, my life expectancy was twelve. I almost died on my second day. As a child with hemophilia, I was told constantly about what I couldn’t do. I learned to ignore limitations. I learned to trust my instincts. Curves, road signs, trucks, double yellow lines…mean nothing to me.

So when I was diagnosed with HIV in 1985, I just kept driving. I went to graduate school, launched a new career, got married … and I had a child.

My daughter was conceived in the back seat of a car. Unfortunately, I was in the front seat at the time. While I watched for passersby, my wife, Karen, performed highly unerotic acts involving a syringe and a Gerber’s baby food jar containing donated sperm.

Karen was convinced she was carrying a boy, so we had not decided on a girl’s name, though we had considered naming the kid after Karen’s grandmother. When my daughter was born blue with her umbilical cord wrapped twice around her neck, when the midwife looked up from between my wife’s legs and said, “she’s floppy,” I used the only girl’s name I had, the grandmother’s name, to call my daughter back into this world, and since she answered, she became, irrevocably, Manya.

We had a plan, my wife and I. I would hold on until Manya was in kindergarten, making it easier for Karen to work and not have to cover huge daycare costs. And then I would die. It was a good plan.

Obviously, though, I knew nothing about parenting. A few weeks after the birth, I was sitting in a friend’s kitchen, staring out the window, when it hit me—it’s not about me anymore. The foundations of my life were suddenly swept away, and yet I found myself more firmly planted on the ground.

Manya had a hard time falling asleep. She had too many questions. She was maybe two when she called me into her room during naptime. Standing up in her crib, she pointed toward the window. “What dat?” she demanded. “The window?” “No, what dat?” “The curtains?’’ “No, what dat?” I look out the window. “The tree?” “Not dat,” she says, pointing at the window, “and not dat,” pointing now at the crib. “What dat?” pointing somewhere in between. And then I got it. She wanted to know about negative space. “That,” I said, smiling at her, “is air.”

Next she wanted to know, “Daddy, who were the first mommy and daddy’s mommy and daddy.” Think about it.

When she was three, she asked, “Daddy, why are we here?” None of my answers fully satisfied her, but I told her what she was experiencing was called existential angst. Now, she could name her anxiety. “Daddy, I have existential angst.”

The more I understood what it meant to be a father, the more I understand my hubris. This kid loved me in a way I had never been loved before, and that was mind-blowing enough, but she also needed me, trusted me. She wanted to shake the world like a snow globe so she could watch all that knowledge fall down from the sky and settle at her feet. And she counted on me to be there, to be both her sidekick and her superhero. But I was going to leave her. For the first time in my life, it seemed, I hadn’t known what was around the bend.

She called me in one night to ask, “Daddy, is Elmo a good monster or a bad monster?” Finally, a question I could answer. “Elmo is a good monster.” I turned to leave. “Daddy, will you keep me safe from the bad monsters?” I turned back and said, “Of course I will.” How could I say anything else? But it was a lie. The monster was already in the house…I had brought it in.

The lie hit me so hard that I began to have regrets about my choice to parent. But those regrets caused a great deal of dissonance. How could I regret the decision that produced my wonderful child?

In 1996, I was giving talks about AIDS to high school classes. In one, a girl asked, “How will you tell your daughter? I am wondering because my father died when I was five.” I didn’t know the answer. So I asked if she had any advice. “Pictures,” she said achingly. “Take lots of pictures.”

I came home after one such talk and read in the paper about success treating HIV with a new drug, Crixivan, the first protease inhibitor. I put my head down on the table and sobbed. “I might live. I might live. I might live.”

I began to believe I could get away with it one more time, this passing on curves. But I hadn’t yet spotted the other truck, the one coming from Karen’s direction.

It first manifested as a scattering of spots on a mammogram. Microcalcifications. Ductal carcinoma in situ. We decided on aggressive treatment. After the mastectomy, the pathology report contained good news. No signs of malignancy, clean margins. Less than two years later, though, a lump appeared under Karen’s arm. Breast cancer survival rates are associated with the number of positive nodes, and in those days they considered more than ten a dire sign. After three months of chemo, Karen had surgery to remove her nodes. She had more than 50 positive nodes.

I asked a doctor friend what she would say if discussing Karen’s case privately with another doctor. She consulted colleagues and then got back to me: two years to recurrence, another two to death. At the same time, information was coming out about the HIV virus developing resistance to the new drugs.

Suddenly, Manya had two parents with fatal illnesses. All three of us were in the same car, rushing headlong into an oncoming truck. How could I have been so arrogant? Surely it had been only a matter of time before passing on curves would catch up with me. And that day was nearly here. I couldn’t imagine a world without Manya, and yet I felt like I had been cruel to bring her into such a situation.

But all I could do was drive Karen to radiation treatments and Manya to birthday parties and soccer games, and try to impart, psychically, energetically, what I know about passing on curves. Maybe they could succeed where I had failed.

At this point, I have to confess something — I am still alive. A couple months ago, I drove down to visit Manya at college. She told me all she was up to. She is the founder and president of a new campus organization that raises money for Third World poverty relief projects. Then there are her regular academic classes, evening Swahili classes, ballet, voice, and yoga. And she had just revised her resume to try to get a summer internship in Africa. I worried about her overdoing it, but so far, she seemed to be holding it together.

Two days later, she texted her mom and me (we are no longer together; and yes, her mom survived, too) to say she had accepted a part in a school play. Her mother couldn’t answer. Her overbooked, overwhelmed daughter was taking on yet one more thing. But I just texted back, “Congratulations.” You see, my daughter, like her father, and in some ways her cancer-survivor mother, doesn’t pay enough attention to limitations. She passes on curves.

All I can do is warn her to slow down and point out the hazard signs. And if she drives over the cliff, I will be there to pick her up, clean her off and put her back on the road. Because that is what a parent does.

Passing on curves is part of who she is. After all, she thrived in a family where both parents expected to die before she left for college. Which begs the question: Which of us was behind the wheel?

And who am I to judge when it comes to passing on curves? I have come to terms with it in myself. It is what I do. It is what I have always done. It is who I am..

When I am in the woods for more than a day or two, everything slows down. I stop talking, I enter a trancelike state. My friends once made the mistake of letting me drive home like that. I was on a narrow, winding highway, a cliff face on one side and a steep drop on the other, making good time despite heavy truck traffic, when my girlfriend looked over and said, placidly, “I trust you. I know you know what’s around the bend. But some of us might be more comfortable if you didn’t pass on curves.”

This is a story about passing on curves.

When I was born, my life expectancy was twelve. I almost died on my second day. As a child with hemophilia, I was told constantly about what I couldn’t do. I learned to ignore limitations. I learned to trust my instincts. Curves, road signs, trucks, double yellow lines…mean nothing to me.

So when I was diagnosed with HIV in 1985, I just kept driving. I went to graduate school, launched a new career, got married … and I had a child.

My daughter was conceived in the back seat of a car. Unfortunately, I was in the front seat at the time. While I watched for passersby, my wife, Karen, performed highly unerotic acts involving a syringe and a Gerber’s baby food jar containing donated sperm.

Karen was convinced she was carrying a boy, so we had not decided on a girl’s name, though we had considered naming the kid after Karen’s grandmother. When my daughter was born blue with her umbilical cord wrapped twice around her neck, when the midwife looked up from between my wife’s legs and said, “she’s floppy,” I used the only girl’s name I had, the grandmother’s name, to call my daughter back into this world, and since she answered, she became, irrevocably, Manya.

We had a plan, my wife and I. I would hold on until Manya was in kindergarten, making it easier for Karen to work and not have to cover huge daycare costs. And then I would die. It was a good plan.

Obviously, though, I knew nothing about parenting. A few weeks after the birth, I was sitting in a friend’s kitchen, staring out the window, when it hit me—it’s not about me anymore. The foundations of my life were suddenly swept away, and yet I found myself more firmly planted on the ground.

Manya had a hard time falling asleep. She had too many questions. She was maybe two when she called me into her room during naptime. Standing up in her crib, she pointed toward the window. “What dat?” she demanded. “The window?” “No, what dat?” “The curtains?’’ “No, what dat?” I look out the window. “The tree?” “Not dat,” she says, pointing at the window, “and not dat,” pointing now at the crib. “What dat?” pointing somewhere in between. And then I got it. She wanted to know about negative space. “That,” I said, smiling at her, “is air.”

Next she wanted to know, “Daddy, who were the first mommy and daddy’s mommy and daddy.” Think about it.

When she was three, she asked, “Daddy, why are we here?” None of my answers fully satisfied her, but I told her what she was experiencing was called existential angst. Now, she could name her anxiety. “Daddy, I have existential angst.”

The more I understood what it meant to be a father, the more I understand my hubris. This kid loved me in a way I had never been loved before, and that was mind-blowing enough, but she also needed me, trusted me. She wanted to shake the world like a snow globe so she could watch all that knowledge fall down from the sky and settle at her feet. And she counted on me to be there, to be both her sidekick and her superhero. But I was going to leave her. For the first time in my life, it seemed, I hadn’t known what was around the bend.

She called me in one night to ask, “Daddy, is Elmo a good monster or a bad monster?” Finally, a question I could answer. “Elmo is a good monster.” I turned to leave. “Daddy, will you keep me safe from the bad monsters?” I turned back and said, “Of course I will.” How could I say anything else? But it was a lie. The monster was already in the house…I had brought it in.

The lie hit me so hard that I began to have regrets about my choice to parent. But those regrets caused a great deal of dissonance. How could I regret the decision that produced my wonderful child?

In 1996, I was giving talks about AIDS to high school classes. In one, a girl asked, “How will you tell your daughter? I am wondering because my father died when I was five.” I didn’t know the answer. So I asked if she had any advice. “Pictures,” she said achingly. “Take lots of pictures.”

I came home after one such talk and read in the paper about success treating HIV with a new drug, Crixivan, the first protease inhibitor. I put my head down on the table and sobbed. “I might live. I might live. I might live.”

I began to believe I could get away with it one more time, this passing on curves. But I hadn’t yet spotted the other truck, the one coming from Karen’s direction.

It first manifested as a scattering of spots on a mammogram. Microcalcifications. Ductal carcinoma in situ. We decided on aggressive treatment. After the mastectomy, the pathology report contained good news. No signs of malignancy, clean margins. Less than two years later, though, a lump appeared under Karen’s arm. Breast cancer survival rates are associated with the number of positive nodes, and in those days they considered more than ten a dire sign. After three months of chemo, Karen had surgery to remove her nodes. She had more than 50 positive nodes.

I asked a doctor friend what she would say if discussing Karen’s case privately with another doctor. She consulted colleagues and then got back to me: two years to recurrence, another two to death. At the same time, information was coming out about the HIV virus developing resistance to the new drugs.

Suddenly, Manya had two parents with fatal illnesses. All three of us were in the same car, rushing headlong into an oncoming truck. How could I have been so arrogant? Surely it had been only a matter of time before passing on curves would catch up with me. And that day was nearly here. I couldn’t imagine a world without Manya, and yet I felt like I had been cruel to bring her into such a situation.

But all I could do was drive Karen to radiation treatments and Manya to birthday parties and soccer games, and try to impart, psychically, energetically, what I know about passing on curves. Maybe they could succeed where I had failed.

At this point, I have to confess something — I am still alive. A couple months ago, I drove down to visit Manya at college. She told me all she was up to. She is the founder and president of a new campus organization that raises money for Third World poverty relief projects. Then there are her regular academic classes, evening Swahili classes, ballet, voice, and yoga. And she had just revised her resume to try to get a summer internship in Africa. I worried about her overdoing it, but so far, she seemed to be holding it together.

Two days later, she texted her mom and me (we are no longer together; and yes, her mom survived, too) to say she had accepted a part in a school play. Her mother couldn’t answer. Her overbooked, overwhelmed daughter was taking on yet one more thing. But I just texted back, “Congratulations.” You see, my daughter, like her father, and in some ways her cancer-survivor mother, doesn’t pay enough attention to limitations. She passes on curves.

All I can do is warn her to slow down and point out the hazard signs. And if she drives over the cliff, I will be there to pick her up, clean her off and put her back on the road. Because that is what a parent does.

Passing on curves is part of who she is. After all, she thrived in a family where both parents expected to die before she left for college. Which begs the question: Which of us was behind the wheel?

And who am I to judge when it comes to passing on curves? I have come to terms with it in myself. It is what I do. It is what I have always done. It is who I am..