By hooks, I mean lines that stand out (and pull the listener in) because they are clever, or lyrical, or profound. Writerly lines. They may introduce a powerful metaphor or capture a meme. The tension is that if you use too many hooks, you will definitely sound too writerly—very few people speak in hooks. So use them only if you think they really work, and only use a few (my rule of thumb is three) for the entire piece. And you will want to save one for your ending..

Monthly Archives: March 2014

Storytelling tip 5: Think about leaving pathos in the wings awhile

Personal storytelling is, by its very nature, a manipulative art. You want your audience to care deeply about what happened to you, and to experience something of what you experienced. And your audience wants to care. Your listeners are there for the vicarious experience your story offers—whether it is hilarity, wonder, emotional empathy, a combination thereof, or something else entirely. The best stories, in my experience, combine humor and pathos, but it is sometimes easier for audience members to connect initially if you don’t hit them with something heavy stuff right away. It might be best to start with something that is interesting and engaging, quirky, astounding, or just plain funny. Or even with a brief infodump But once they are fully engaged, once you have drawn them into the story, once they have come to know you a little and to trust you, they are more likely to follow you into complicated and unexpected territory. I am offering this tip as something to think about, not a rule; there are pieces in this collection that start with emotional scenes.

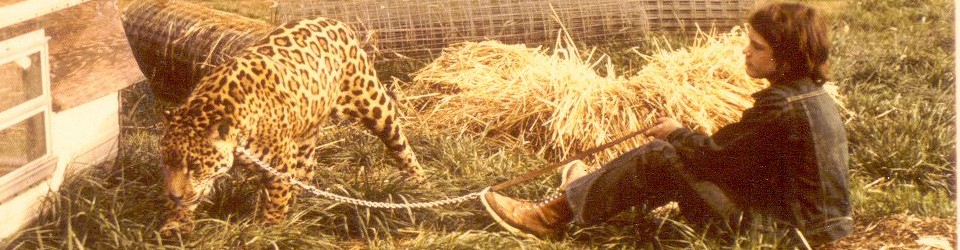

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Storytelling tip 4: Dump your info at the beginning—or not

Your listeners likely will need some basic information to help them understand the context for the story. Exactly what they need will vary; examples might include how old you were when the story took place, or how certain characters came into your life. It is ideal if you can weave this information into the flow of the narrative, revealing it unobtrusively just as the listener needs it, but that is not always possible. You may need to tell and not show—you may need what some writers call an infodump. In my case, an infodump might sound something like: “When I was in junior high, my parent’s divorced and my mother married a man named Mike who collected exotic animals, which is how I ended up spending my high school years living on a tiger farm.” A short infodump can sometimes be used to great effect in the middle of the story to emphasize some particular development—for example, I might withhold the information about having hemophilia until I come to a place in the story where injury seems imminent. But by and large, infodumps are like speed bumps—you want to avoid slowing down the narrative once the audience is engaged, which means you should think hard about where you place an infodump. Consider putting it at the start of the story. That way you can get through it, and then start to pick up steam as you get deeper into the piece.

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Storytelling tip #3: Don’t be too writerly—unless you are

A common dis on personal stories, especially those that have been scripted in advance, is that they are too writerly. And for good reason. The idea is to tell believable stories, not to create high art. You can avoid sounding writerly by choosing short Anglo-Saxon words; composing simple, declarative sentences; avoiding obvious contrivances like long alliterative strings; and writing to a specific grade level (fifth, say, or better yet, third). In short, don’t show off and don’t try too hard. Big words from the Romance languages, inverted sentences with lots of independent clauses hanging off them, and overworked metaphors can create the impression that the audience is there to relate to the writing, not the storyteller. Always remember that at a personal storytelling performance, there is no fourth wall. That said, however, it is important to keep in mind the reason for such advice. If there is one element that is the key to personal storytelling above all others, it is authenticity. If using big words and technical terms and lyrical phrasing is who you are, if that is how you talk when you are sitting around a living room with your closest friends, then trying to sound like someone you aren’t might actually make you come across as less authentic. Don’t overreach, but don’t try to relate to the audience from behind a false persona, either

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Excerpted from Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

Tip for Storytellers #2: Pay attention to tone throughout

You—meaning the narrator you, the storyteller you—are a character in the story just as much as the version of you at the center of the story. I tell a lot of stories about my childhood and I started performing personal stories in my fifties; both the child protagonist me and the fiftysomething narrator me are characters. Careful characterization is important. The narrator needs to be trustworthy, and trust is largely about reliability and authenticity. Your narrator’s character will be conveyed by the voice you use and the tone of your comments. If you want to be snide and cynical, no worries, as long as you are really funny while you’re at it. People can appreciate caustic humor, sarcasm, and irony. But if you want to take people on an emotional journey, they will want to feel like they are in safe hands and that there will be a pot of wisdom, or at least a token of insight, at the end of the rainbow. If your tone is about being forthright and thoughtful and self-aware and compassionate, and then you get snarky even for a moment, your audience may find this jarring. At the same time, the tiniest observation, something that feels like a throwaway line, can add to your narrator’s credibility.

Excerpted from the Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

.

Excerpted from the Lions and Tigers and AIDS! Oh, My!.

.

Storytelling tip #1: Start with a script–but not a sacred text

People can tell amazing stories without any special preparation, but I rarely improvise without a score. Ten minutes is a long time, and I want to make the best of it. Writing, rewriting, and editing helps me do that. Most stories traded across bars and campfires and kitchen tables take far less than ten minutes to tell, and people typically lose interest when a companion monopolizes a conversation for ten minutes at a stretch. The last thing you want to do as a performer is extend a natural five-minute story out to ten minutes just because that was the timeslot given you. Ten minutes allows for and even encourages the inclusion of multiple interrelated stories. Stories can be tied together by a theme or a common character, or smaller stories can be embedded into a main storyline, or stories can be allowed to weave in and out of one another like the strands of twine that make up a rope—reinforcing each other in the process. Almost every piece in this collection can be broken down into several sub-stories that conspire to create a whole. Writing a piece down is a good way to play with structure, to figure out how to assemble the pieces, to find the shape of the story..