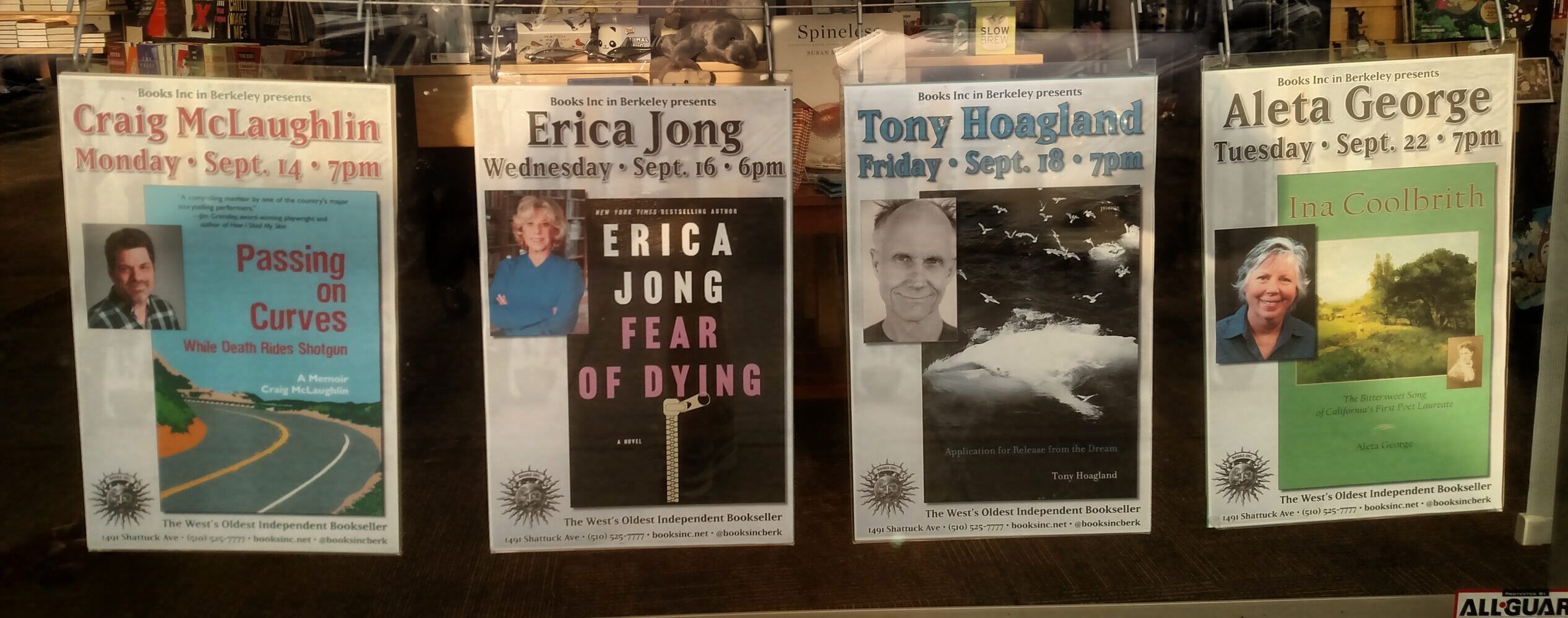

In gripping essays from his stage performances, Craig McLaughlin travels a road where death lurks around every turn. At birth, he almost bleeds to death because of hemophilia. Despite the odds, he survives to adolescence but finds himself living on an exotic animal farm where the humans can be more menacing than the tigers. As a young adult he contracts HIV from contaminated blood products, and later struggles to care for his wife with breast cancer while disease threatens to orphan their daughter.

McLaughlin shows tremendous reverence for both life and death. Readers will fear for him, cheer for him, and marvel at his resilience and ability to recover from misfortune.

Stories include:

• Being trapped in a pickup cab with an out-of-control chimpanzee.

• Dreaming of a demon that forces him to confront his own death.

• Gearing up for a gun battle with the Hells Angels.

• Comforting the man his mother and stepfather kidnapped.

McLaughlin intuitively navigates blind curves to arrive at a destination rich with insight, compassion, and humor. Told with unflinching honesty, Passing on Curves is a memoir of inspirational courage.

Purchase Kindle edition from Amazon.

Praise for Passing on Curves:

While Death Rides Shotgun

Author Craig McLaughlin was born a hemophiliac. He’s been ‘riding shotgun with death’ since birth, facing the risk of bleeding to death from common injuries. But rather than lead a life of caution, McLaughlin’s purpose is a life well lived, and not necessarily one well protected. Passing on Curves While Death Rides Shotgun is a memoir replete in risk-taking adventures and living well…

This is a story about navigating life when the unexpected becomes normal. One doesn’t expect caring for exotic animals to enter into this picture — but, it does. One doesn’t anticipate that a memoir so replete with medical challenge could also be steeped in hope — but, it is.

— Midwest Book Review

The early stories about the makeshift zoo are particularly memorable…. McLaughlin relates them so honestly, with the right mix of emotions. What’s here is good stuff, and unique.”

—Foreword Reviews

A compelling memoir by one of the country’s major storytelling performers.

—Jim Grimsley, award-winning playwright and author of How I Shed My Skin

“McLaughlin suggests that what sets us apart as humans is that we tell stories…he’s got some doozies. Open this book and you’ll see what I mean.”

—Jim Lynch, award-winning author of Truth Like the Sun

“A born storyteller, McLaughlin grew up with so much to fear, he became fearless—particularly in digging into the painful truths and revelations that make this a remarkable collection of personal essays.”

—Laura Fraser, New York Time best-selling author of An Italian Affair

“Written with compassion, vulnerability and economy…his stories are like polished jewels.”

—Starhawk, best-selling author of The Spiral Dance and The Fifth Sacred Thing

“McLaughlin has taken some of his rawest and most fascinating monologues and anthologized them into this page-turner of a book..”

—Barry Yeoman, author of The Gutbucket King